One of the threads that The Elusive Shift follows is the development of typologies that sorted players, or sometimes game designs or playstyles, into categories that reflect what kind of experience people want to have when they sit down to game. These form a significant component of contemporary RPG theory. I myself was surprised, doing research for the book, to discover threefold model typologies already discussed in the wargame community years before Dungeons & Dragons came out. In these early discussions, we can see the roots of much of the RPG theorizing that would follow, like the classic fourfold Blacow model, shown in a later visualization above.

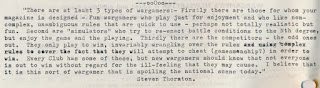

Whenever a group of people around tabletop plays a game, participants may have conflicting approaches to play. Early wargamers had long observed a trade-off in game design between realism (attempting to design systems that simulated real conflicts with as much detail as possible) and playability (the countervailing drive to build systems that are simple and unambiguously executed), and it wasn't long before they observed the potential for tensions in play between people who prized one goal over the other. By the beginning of 1971, Steven Thornton had perceived that there was more nuance to this than a simple dichotomy:

Thornton saw three categories of wargames: "simulators" who are obsessed with realism; "competitors" who engage in endless rules lawyering for the sake of securing victory; and then the mainstream of "fun" wargamers who are doing this casually "just for enjoyment." Thornton had learned already of the "ill-feeling" that extremist views could cause, and that these could be a threat to the very hobby. Nor did Thornton's words fall of deaf ears: they would be picked up by Fred Vietmeyer a year later:

But Vietmeyer has a more pluralist view of this typology, arguing against what would later be called a "One True Way", as "for one type of player to place his own viewpoint as superior to another's hobby enjoyment is simply being too egotistical." Some players might want to invest hours in painting meticulously researched miniature flags and uniforms for the sake of realism; others might find that "a waste of time." Vietmeyer would return to this theme in another article in The Courier two years later, right at the time that Dungeons & Dragons hit the shelves.

The release of D&D drew another community into dialog with wargamers: science-fiction and fantasy fans. Their presence and incentives upset the traditional typologies of the wargaming community, to the point where people began to see a new type that had come to the table: story focused-gamers. As Lewis Pulsipher wrote in 1977:

Pulsipher sees a distinction between those who wanted to play D&D "as a game" and "those who want to play it as a fantasy novel." His "D&D Philosophy" is very concerned about the lack of agency that players might experience when a game session is too tightly pegged to a narrative, so that "the player is a passive receptor, with little control over what happens." But many in science-fiction fandom sought a way to engage with stories through RPGs that would strike a balance between a game experience and the high drama of fantasy literature.

By 1980, Glenn Blacow had developed his famous fourfold model, which retained the traditional wargame/simulation type, the power-gaming/competition type (originally Blacow called it "ego-tripping"), but introduced in place of Thornton's "fun" wargamer two new categories: role-playing and storytelling. A contemporaneous visualization of it is shown at the header above. Blacow saw the "interaction of these four elements" as determining the "feel" of the game.

Blacow knew well that these "forms" all manifested to some degree in any tabletop RPG, it was really a matter of which dominated, and how much of each was necessary to give a particular player a satisfactory experience -- perhaps the definitive refutation of a "One True Way". His model immediately revolutionized the way people talked about RPGs in the fanzines of the day, which were the closest thing people had at the time to Internet discussion forums.

Various corollaries or extensions of Blacow's model appeared through the 1980s (including the visualization above, from Different Worlds, which shows some forms as mutually-exclusive). By the time the Internet came into its own, and those ideas moved onto forums like Usenet, we can see the "threefold model" of gamist, simulationist, and dramatist (or narrativist) agendas begin to take hold. These would be recontextualized by the Forge in the GNS model. But The Elusive Shift shows this RPG theorizing as existing in a continuum that predates D&D, which was steered by the messy reconciliation of traditional wargamers with the new story-focused gamers who entered the hobby from science-fiction fandom. Typologies like this demonstrate why it is impossible to develop the perfect RPG -- the tension between the "forms", however, has fueled tremendous creativity in RPG design for the past four decades.

Hi, Jon. It's a weird coincidence, but I just wrote a blog post that discusses almost the same thing, looking at some of the same sources, as this post. My discussion is more about "player kicks," but the typology discussion is similar. I swear I did not see yours until after I wrote mine, but I will add a link to yours for the reader's interest. I don't go back before Pulsipher in '77. I hope you don't mine my sharing this link in case others want to look at it:

ReplyDeletehttps://lichvanwinkle.blogspot.com/2021/01/knowing-your-players-and-their-kicks.html

No problem, there's a ton more to be said about than I said here. There are many, many intermediaries between Blacow and Usenet GNS, that's for sure. And a ton since GNS as well. There's some good overview material in the Routledge RPG Studies handbook.

DeleteThanks, Jon. I'm sure there are a lot more lists of types. I'll take a look at the Routledge book, too.

DeleteGreat article, can't wait to read more in Elusive Shift.

ReplyDeleteMore informations also in Role-playing games studies, Zagal & Deterding, 2018 (pages 201-203). For example with «WARriors vs GAMErs» (Steve Perren in 1970)

The Routledge book borrowed that one from PatW (pg300 fn169).

DeleteOoops, of course... I used my lacunar notes instead of the original document. May the citation be with your great PatW!

DeleteThere was a big study of the hobby game world as a whole back in 2006, with GAMA, that found a variety of motivations for hobby gamers, including RPGs and wargames....

ReplyDeletehttps://www.armchairdragoons.com/articles/research/motivations-of-hobby-game-players/

Love your latest book, btw. I know this was a major (the major) theme. It was funny reading it, as I lived through a lot of it. :-)

ReplyDeleteJohn Peterson again starts another good topic.

ReplyDeleteAnother major difference is between the campaign view of the universe, that is the world-building, and the player-centric view of the universe, which is more concerned with the trials and tribulations of a single set of adventurers. This becomes more evident as gaming groups evolved from the Game Master and players. With a single GM, there is a bias towards the players and their tribulations, but the main works and main game systems already were taking the bias towards the campaign view of the universe whether it is Greyhawk or Jaynar (which was developed from Ohio and transplanted into MITSGS.) The tension between the world and the players sets up tension because the game's master maybe be thinking of a world while the players are thinking of themselves as heroic, or anti-heroic, key figures.

This even goes to GM's - one GM might have a different way of making magical weapons that focuses on a pyramid with +1 items and only a few +5 whereas another GM might keep ordinary weapons the norm with a few ungodly magic items. (Think Lord of the rings) One can see the difference by the character sheets that come from the two campaigns. Even more so if the two GM's allow trading between the worlds, one supplying +1’s in abundance for truly rare magical items where the other side sees the advantage of having +1 armed contingents where none exists.

Bear in mind that successful campaigns tend to be a meeting somewhere in the middle, where the GM aspires to create a specific sense of place whereas the players want to simulate a particular character, often the same one between many different campaigns. The player is the Thief or Barbarian from a mixture of the books and fantasy that they have and they are looking to re-create that in whichever environment the GM offers.

You should talk about other gatherings of individuals. The obvious one is computer games but also of interest would include LARP/SCA/Medieval Faires, Hacking, Writing etc.

ReplyDeleteA very important point for the hobby and industry: "Typologies like this demonstrate why it is impossible to develop the perfect RPG"

ReplyDeleteI came across the 4-fold way in an early edition of _Different Worlds_ and with one addition I have always found it correct. That one addition is the metagamer who plays in order to mess with the heads of the DM and other players.

ReplyDeleteIn a more humourous vein, there is also the real men, real roleplayers, loonies, and muchkins list.

ReplyDelete